Understanding Trade and Capital Flows: Part 2

Greece Outside of the Eurozone

Imagine the dissolution of the Eurozone, with all member countries reverting to their own national currencies and regaining control over both their foreign exchange and interest rates. How could Greece go about rebuilding its productive capacity under these conditions?

Interest Rates and Investment

If Greece sets high interest rates, foreign investors will be attracted by the potential for high returns. While financing costs for both the government and private sectors would be high, this would encourage disciplined investment—only the most profitable projects would be able to meet the high borrowing costs.

With borrowing becoming more expensive, Greeks would rely less on debt to finance their purchases and investments, shifting instead to savings. Additionally, Greeks would find it more appealing to save, as they could earn a higher return on their savings by investing in government debt. It’s far more attractive to save your money when you’re getting a 10% return rather than just 3%.

The Impact on Consumer Spending

While high interest rates may make purchases like homes and cars seem unaffordable in the short term, they will help correct asset overvaluation over time. When interest rates are low, borrowing is cheaper, leading consumers to finance more of their consumption. This drives demand, especially for high-value assets like homes and vehicles. With more consumers purchasing these items, higher demand drives up prices, making them less affordable.

However, as borrowing costs rise, people are more likely to save for a larger down payment or to pay upfront, which reduces the number of buyers and subsequently lowers demand. With lower demand, prices will decrease, making big-ticket items like housing more affordable over time.

Additionally, debt-based demand results in consumers paying a much higher price over the long term, as they finance their purchases over decades. High interest rates shift the focus from debt-based spending to savings-based spending, helping to prevent price bubbles and ensuring that consumables (like homes and vehicles) remain affordable in the long run.

The Impact on Businesses

High interest rates significantly affect businesses. Elevated borrowing costs make companies more selective about taking on loans, encouraging them to finance investments using retained earnings or profits rather than incurring debt. As a result, businesses are encouraged to focus on long-term investments in durable assets that generate sustained returns, while short-term investments become less attractive due to the higher cost of capital and borrowing. This shift helps reduce speculation and risky investments.

Furthermore, companies with financial discipline can reinvest their savings to grow their businesses, benefiting from prudent capital management in a high-interest environment. For individuals starting businesses, the higher cost of borrowing requires a greater personal investment, which fosters more careful and conservative investment decisions.

The Impact on Governments

When interest rates are low, governments can issue more debt and spend more freely than they would if capital were more expensive. However, when interest rates are higher, governments are incentivized to spend more responsibly. They are also more likely to rely on tax revenue rather than debt to fund their activities, promoting fiscal discipline.

With higher interest rates, if the government does not exercise financial restraint, it could face high levels of inflation. This would result from increased spending required to meet the interest expenses on non-productive expenditures.

Governments must adhere to the principle that debt should only be incurred if the borrowed funds are used for investments that generate enough additional revenue to eventually repay that debt.

Central Bank Flexibility

While central banks cannot fully control interest rates—because market forces always play a role (as discussed in Part 1)—they can significantly influence rates through their monetary policies, especially when coordinated with government actions. This leverage comes from the fact that government debt is typically purchased by regulated entities such as banks, insurance companies, and pension funds, which are often legally required to hold a designated portion of government bonds. Domestic regulations also incentivize these institutions to maintain demand in the bond market, ensuring there is always a buyer, even during fiscal stress.

If government debt fails to attract buyers at a set rate, central banks may resort to debt monetization—purchasing government bonds directly—as a last resort. While this can help provide liquidity, it carries risks. Debt monetization may signal potential inflationary pressures or fiscal instability, which can undermine confidence in the currency and increase the perceived risk of future government debt.

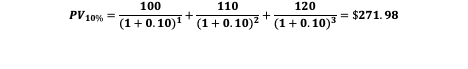

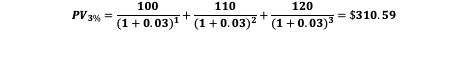

When central banks coordinate with government policies and lower interest rates, they can generate an economic cushion for consumers and businesses during downturns. This allows consumers and businesses to refinance at lower rates, reducing their debt payment burdens or potentially pulling equity from their appreciating assets. Lower interest rates make future cash flows more valuable, which tends to increase asset valuations. For example, if a business is expected to generate $100 in Year 1, $110 in Year 2, and $120 in Year 3, the present value of that cash flow would be:

• At a risk-free rate of 10%, the present value is $271.98

• At a risk-free rate of 3%, the present value is $310.59

This demonstrates how lowering interest rates can increase asset valuations. As Warren Buffett famously said, “Interest rates act as gravity on the value of financial assets.”

However, if central banks manipulate interest rates too aggressively to inflate asset values, this could undermine confidence in the economy. In such cases, the market may view the central bank’s actions as unsustainable, leading to a lack of faith in the currency and the economy as a whole.

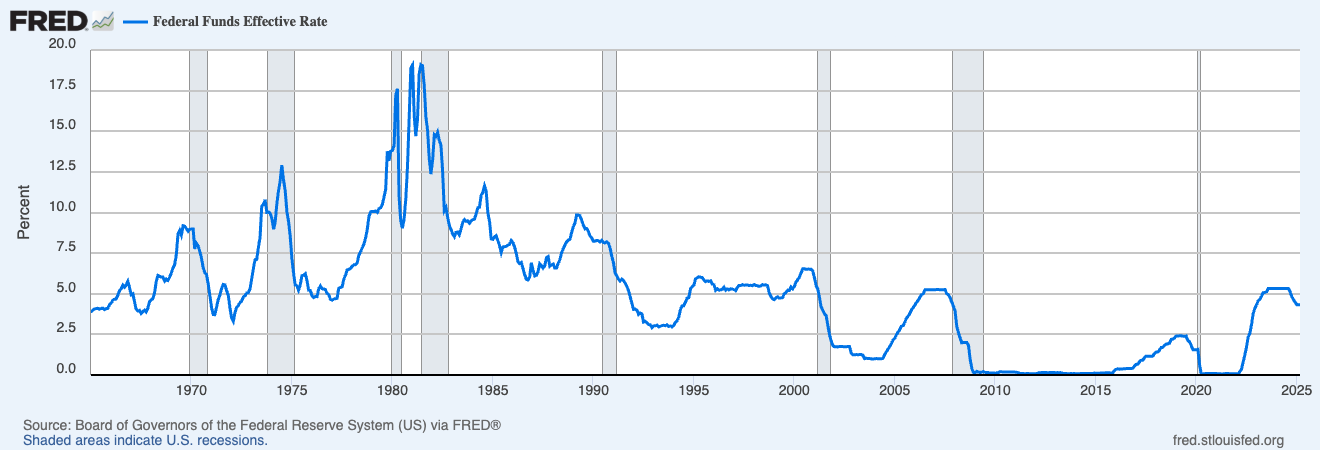

Here is a chart of the Fed Funds rate set by the US Federal Reserve over the past 60 years:

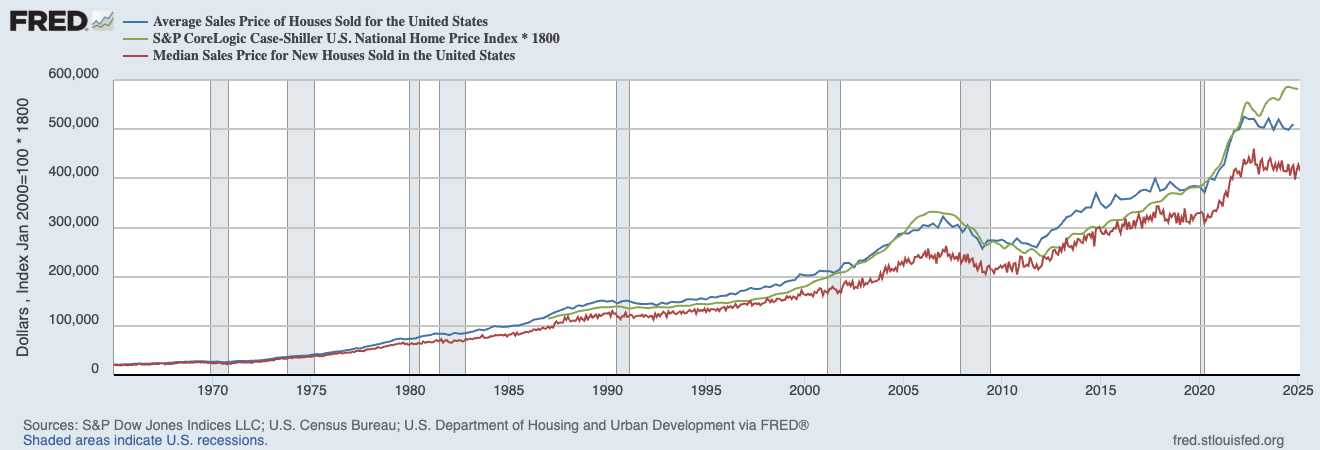

This rate is the benchmark for short-term borrowing in the U.S. Here’s a graph of home prices over the same period:

Notice any trends?

Other Considerations When Dealing with High Interest Rates

High interest rates would likely lead to an appreciation of Greece’s currency. Since Greece is still in the process of developing its economy, it will need to direct investment into the most productive sectors that can generate the higher returns necessary to meet interest expenses. In this case, currency appreciation could be beneficial for Greece. The country will need to import goods and products (such as concrete, steel, coal, etc.) to industrialize, and a stronger currency would make these imports more affordable compared to a weaker currency. The trade deficit resulting from the industrialization process could be offset by the capital surplus from foreign investment and loans.

To protect emerging industries and reassure foreign investors, Greece could introduce tariffs and/or subsidies. These measures would help support developing industries until they reach the scale necessary to compete with established foreign markets. Tariffs and subsidies should be used to protect young industries or those undermined by unfair trade practices. However, older, outdated industries should be allowed to fail. Differentiating between these two groups is often debated. Assuming fair trade practices (equal labor standards, environmental regulations, tax policies, etc.), manufacturing products closer to where they will be consumed is usually more cost-effective due to savings in logistics and warehousing associated with fragmented supply chains. Additionally, tariffs generate tax revenue, which can be reinvested into these industries, possibly through subsidies or public infrastructure development.

When Greece was in the Eurozone, it struggled to export its products because the demand for euros, driven by Germany, made the currency too expensive for Greece, which had lower labor efficiency. This issue would persist under the new system, so Greece would need to support existing industries during this transitional period of economic development. Tariffs and subsidies could be effective tools in this regard. Additionally, the increased domestic demand generated by industrialization could help create a market for these industries. It’s important to note that currency appreciation and depreciation occur relative to foreign currencies, meaning that domestic demand, which does not require foreign exchange, would not be affected by these changes.

Other fiscal reforms can also have a significant impact. Reducing taxes for businesses investing in Greece will boost company profits, making the country more attractive for investment. Since high interest rates encourage development through savings rather than debt, the government should consider tax reforms that incentivize saving rather than penalizing businesses. For example, businesses in the U.S. are taxed on profits, often forcing them to invest all earnings, even in nonproductive activities, to avoid taxation.

By implementing these measures, Greece could improve labor efficiency, lay the foundation for long-term growth, and ultimately create a more productive economy, leading to higher wages for workers and the ability to generate savings. Over time, Greece could begin to reduce tariffs and lower interest rates. As development progresses, the tax base and revenue would grow, eventually leading to balanced trade and a stable financial position.

Conclusion

This essay has explored the complexities of international trade and finance through Greece’s hypothetical potential departure from the Eurozone. It examined key economic concepts such as monetary sovereignty, interest rates, foreign investment, and the Balance of Payments.

The example of Greece highlights the challenges and opportunities that arise when a country loses the ability to manage its own currency and interest rates. While the Eurozone offers a shared currency and economic unity, it also limits member states’ ability to adjust to trade imbalances or economic shocks. The Balance of Payments framework provides insight into how capital flows, trade deficits, and foreign investments interact in a globalized economy.

This framework is applicable to broader questions about how countries manage their economic relationships in an interconnected world and navigate the complexities of global trade and finance to achieve sustainable growth.

Next, we will discuss the Trump tariffs, considering the role of the U.S. dollar as the reserve currency, and the current economic dynamic.